If you’ve played any video games at all over the last forty years or so, you can’t have escaped the influence of Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone. These two legendary filmmakers who redefined the image of samurai and cowboys in pop culture also defined many of the visual motifs, character archetypes, and narrative tropes we still see plastered all over the games industry today, decades after their deaths. The concept of the cool brooding hero driven by a strong sense of justice, drifting from town to town and becoming embroiled in local affairs before heroically saving the day—basically every game ever made—is so entrenched within the very fabric of this industry that it’s never going away.

What a shame, then, that it’s a part of their legacy they were both largely oblivious to. I can’t imagine Kurosawa could have conceived of the notion of wandering Ronin simulator, Ghost of Tsushima, and when Leone died in 1989, the very idea of a game like Red Dead Redemption would have seemed like pure fantasy. There’s no greater shame, though, than that neither of them lived long enough to witness the absolute nonsense and unadulterated joy that is Samurai Western.

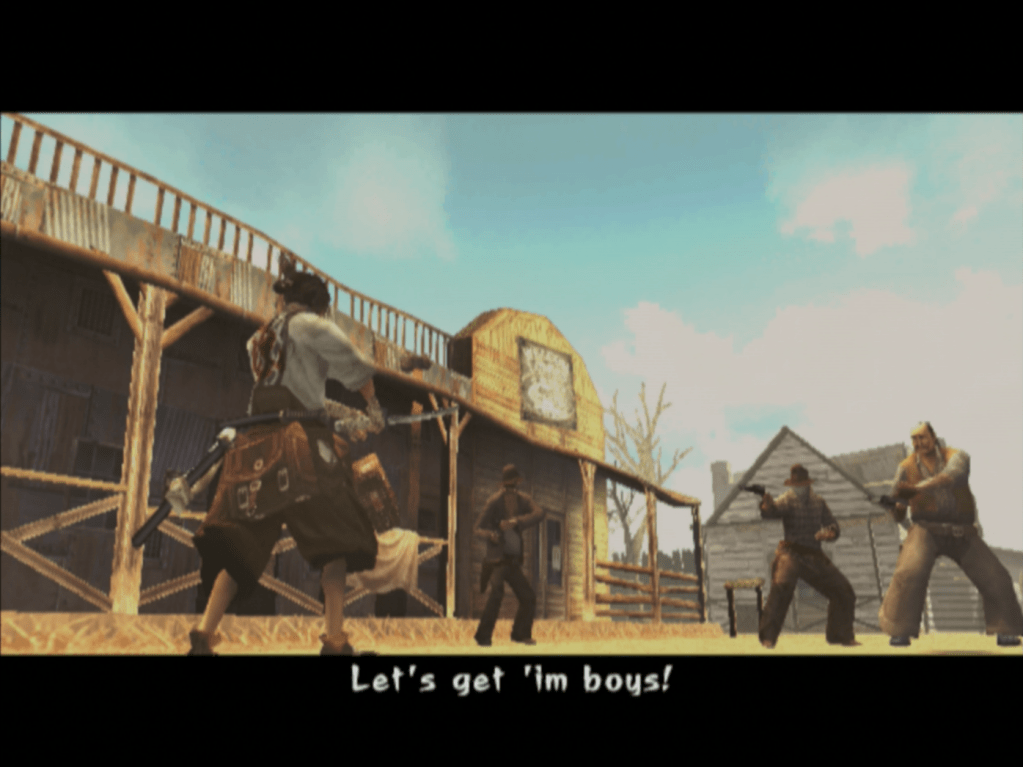

Guided by an unspoken code of honour, a mysterious stranger strolls into a small, windswept frontier town in the American Old West. You know how this goes. Except this time, he’s wearing a kimono and wielding a katana. Cue lingering shots of tense standoffs and cocky gunslingers thinking they’ve got the upper hand before being dispatched in a flash of steel, followed by a cool, slow sheathing of the sword, surrounded by toppling bodies.

Samurai Western is a (very) loose re-imagining of both Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars through the lens of mid-2000s Japanese action game design, taking the protagonist of one and dumping him in the world of the other. Whether it feels like playful homage or cheesy, derivative pastiche will depend on your tastes, but for me, it’s clear that Tenchu developers Acquire had a lot of love and respect for both classic westerns and samurai cinema that really shines through here. It’s all presented with a big wink and a nod, and it pulls off this inherently ridiculous premise with an effortless, quirky cool—a very hard tone to get right. The story itself is nothing to write home about, but the love that’s been poured into its presentation is infectious.

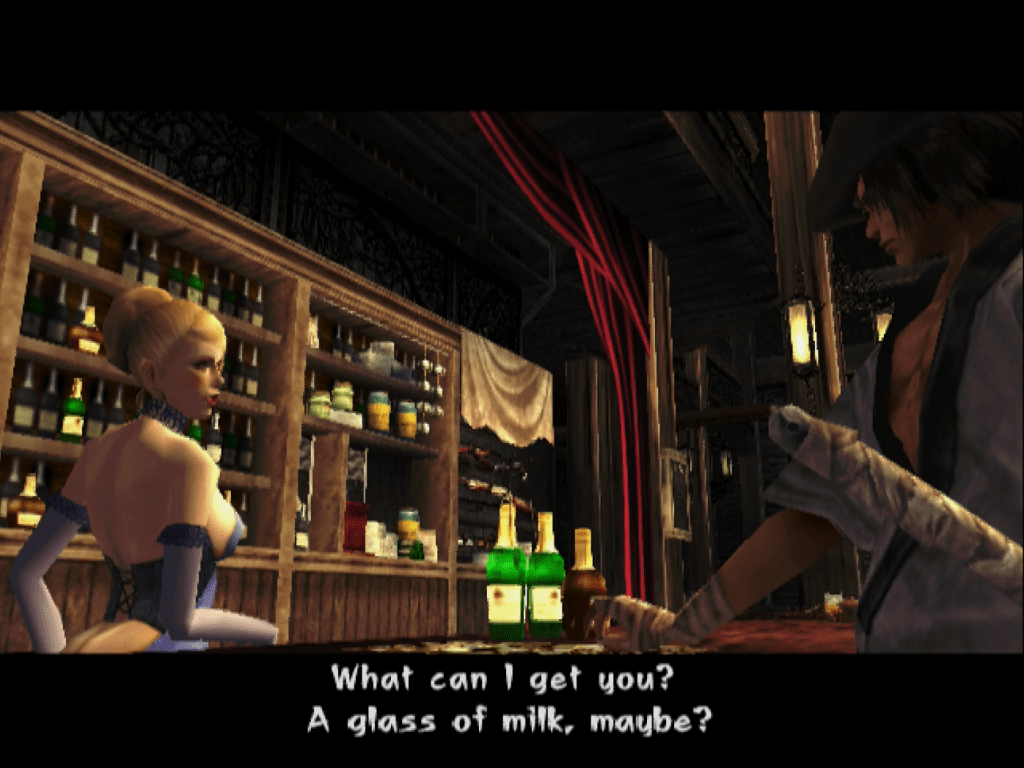

For a budget title, an unusual amount of attention—and presumably money—has been paid to creating a striking and cohesive aesthetic that runs throughout the whole production. A brilliant intro movie riffs on the familiar stark black and red colour scheme synonymous with Leone’s spaghetti westerns. The soundtrack is an appropriately twangy cocktail of guitars, banjos, and harmonica mixed with traditional Japanese instruments, making for a unique mix of sounds. Cutscenes are suitably cinematic too and well directed, with a great voice cast who are clearly in on the joke, including the main character, voiced by Japanese actor Masato Amada, slipping in and out of his native tongue, which is a nice little touch. Each chapter is also bookended by a moody narration from various in-game characters, following the exploits of our stoic hero and recounting them with atmospheric gravitas. The game has a great sense of style.

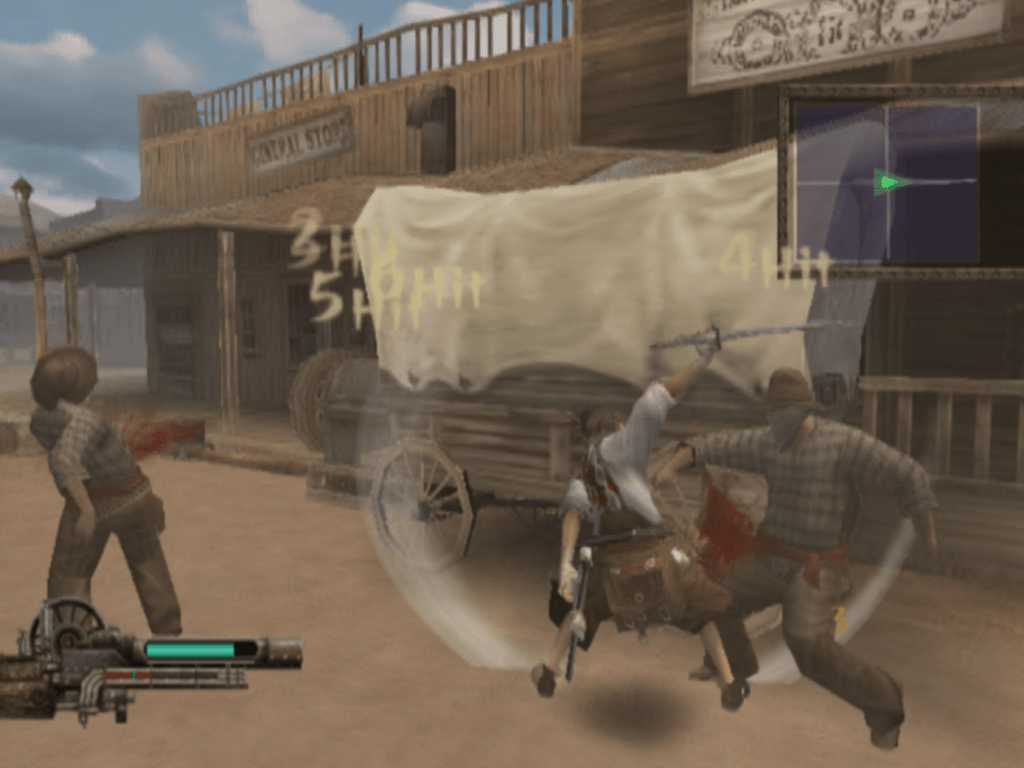

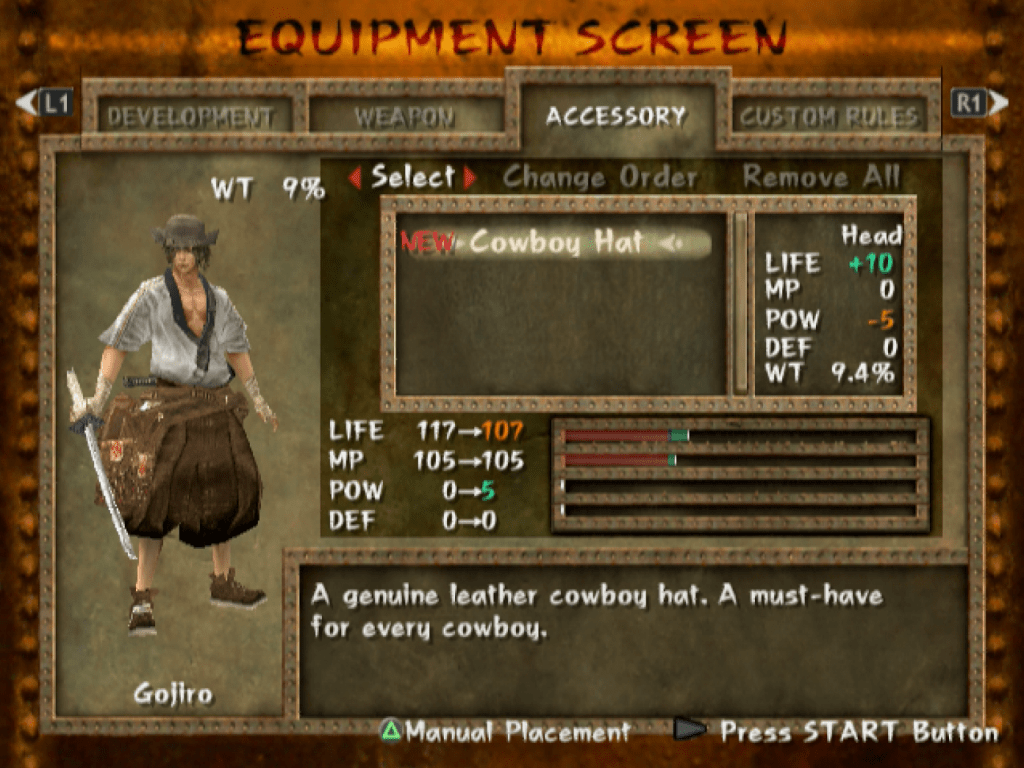

The flow of play is very straightforward. You enter one of sixteen small, linear stages and fight through pockets of gun-toting enemy spawns using simple sword combos, with the goal being to clear each stage as quickly and efficiently as possible to hopefully earn a high score. At the end of each mission, your score is tallied up, and experience points, weapons, and equipable items are awarded depending on your rank.

In combat, racking up enough combos allows you to unleash “Master Mode,” turning you into a one-hit kill-dealing death machine for a limited time, which is extended slightly with every kill. Tactical timing of master mode deployment for maximum effect is key to finishing stages quickly, and each weapon type bestows a different effect while it’s active, adding another small layer of strategy. The unique hook of the combat system is a spinning dodge move that allows you to avoid bullets, quickly close gaps between yourself and your enemies, and, when timed properly, deal devastating counterattacks, which are essential for some of the tricky boss encounters.

The game often throws a large number of enemies at you or places you in very confined spaces, meaning that in practice, it’s almost required that you never stop dodging, making movement a ludicrous perpetual whirlwind of motion. It looks awesome at times, bizarre at others, and is both great fun and hilarious, which I think is the point—we’re not meant to take this game about cowboys versus samurai seriously. But in truth, part of me wanted to play the quiet, coiled menace we see in the cutscenes, not this hyperactive Crash Bandicoot-looking fella. I’m never normally one to advocate for style over substance, but the combat could maybe have used some of that cinematic flair this team’s clearly capable of.

While combat is the meat of this game, the key to getting the most out of it lies in the unbelievably generous amount of unlockables. New stages, weapons, items, and playable characters are collected by reaching certain XP thresholds, beating high scores, finding in-game “wanted” posters, and, most interestingly, completing sets of optional “custom rules” that can be applied manually to each stage after completion. It’s impossible to collect everything on a single playthrough, so repeating stages on higher difficulties and with custom rules is essential. There’s nothing in-game to tell you how to unlock this treasure trove of goodies, so I checked a guide and started chasing down specific challenges, forcing me to tease more nuance out of its systems as the difficulty ramped up. Like the very best action games, there are layers to the combat that aren’t initially apparent, and I found that the game significantly improved the more I played it.

I can easily see how a first playthrough might leave someone with a mediocre impression, and the raft of negative reviews perhaps suggests that most critics didn’t play beyond seeing the credits. The game is instantly fast and fun, but the craft that’s gone into the combat, encounter, and stage design isn’t immediately obvious the first time through. Like the arcade brawlers of the ‘80s and ‘90s on which this genre’s foundations were built, the game is short, but designed to be highly replayable. In the pursuit of high scores on its more challenging settings, the potential for high-skill manipulation of its systems becomes clear and the seemingly random enemy placement reveals itself to be far more considered, with just enough time and space between spawns to chain Master Mode strikes as you blaze through levels in record time. Eventually, I did reach a point where I felt more like the ice-cold, unstoppable force of nature portrayed in the cinematics. It took a while to get there, but the payoff was worth it.

I ended up loving my time with Samurai Western, and it more than justifies its ubiquity on all those YouTube PS2 “hidden gems” videos. What at first appears to be wonderfully silly, uncomplicated fun later reveals itself to be a game of real craft and surprising hidden depth—even if you do have to work perhaps a little too hard to unearth it. Kurosawa and Leone would be proud…maybe.

Leave a comment