Puzzle game connoisseurs have not so much been ‘eating good’ this month, as they have Cookie Monster-ing an entire dump truck of McVities variety packs into their delirious ‘can’t-believe-how-good-we-got-it’ googly-eyed faces. “Om nom nom nom,” and all that. Indie developer Cicada Games has been baking Isles of Sea and Sky for over five years and is ready to serve it fresh from the oven. But is it a luxuriously gooey double chocolate cookie or a stale old bottom-of-the-barrel Hobnob? With the only certainty being that I should have written this review after lunch, let’s find out.

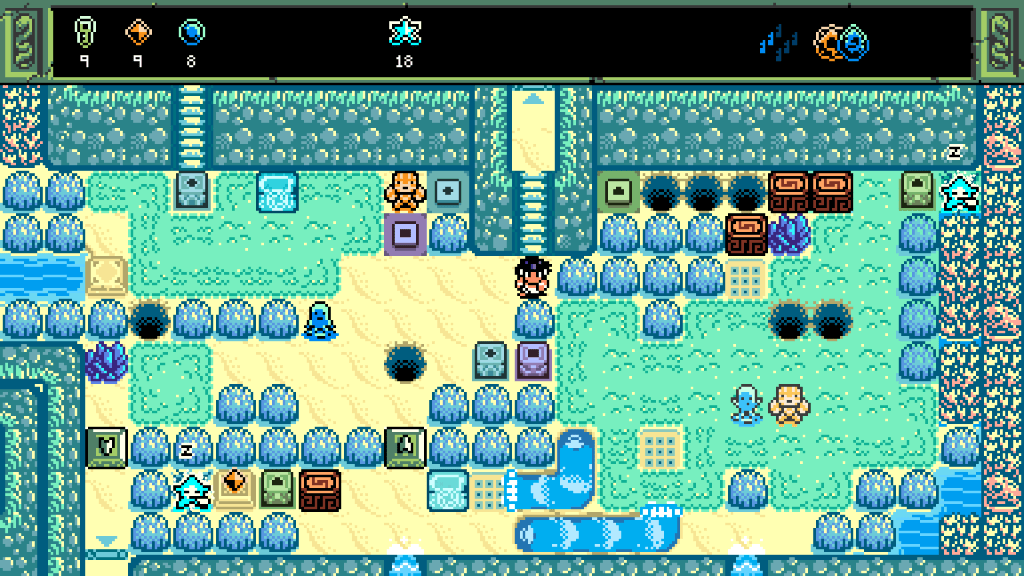

Isles doesn’t try to hide the sources of its inspirations, proudly lifting the design of the 1989 classic block pushing puzzler Chip’s Challenge (and rightly so), and then, with the benefit of over three decades of game design wisdom, draping it around a metroidvania-style structure and sprinkling its puzzles over a top-down Zelda-like overworld.

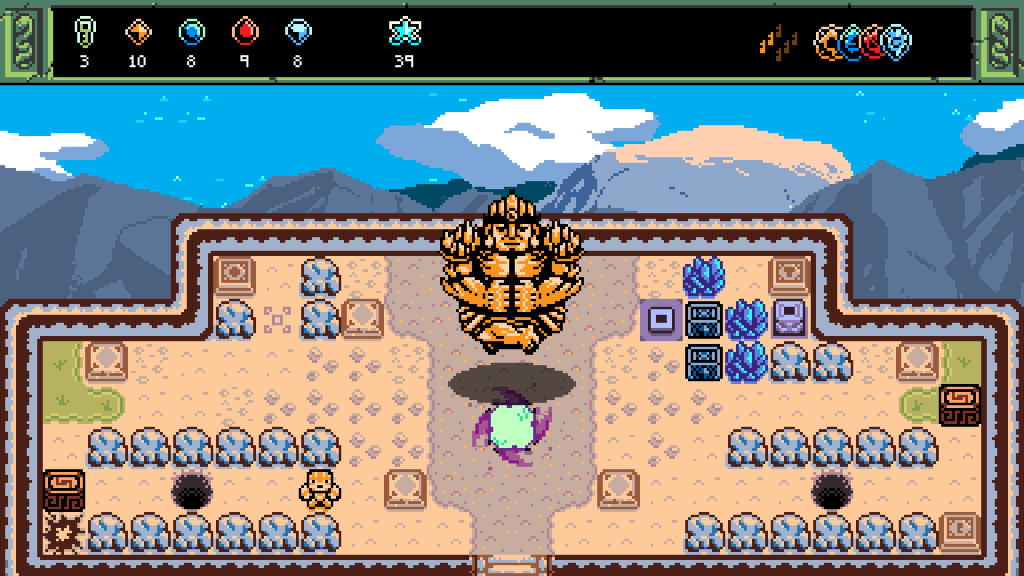

An elegant wordless introduction begins with your character washing up on a small starter island before you learn the basic mechanics through some clever gameplay-led tutorials. At the island’s centre is an elaborate locked door, adorned with four coloured icons with highly suspicious-looking empty recesses. If you’ve played a videogame before, you’ll recognise this as your primary goal and motivation. It’s begging to be opened, but you’ll need to conquer the world’s four main islands to discover what lies beyond, and unfortunately, each is absolutely riddled with puzzles and mysteries.

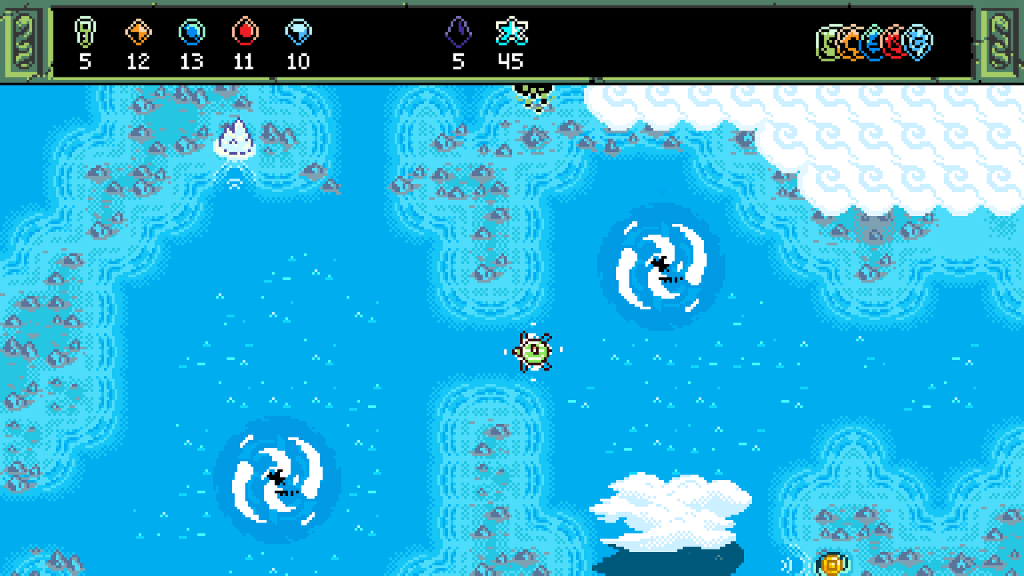

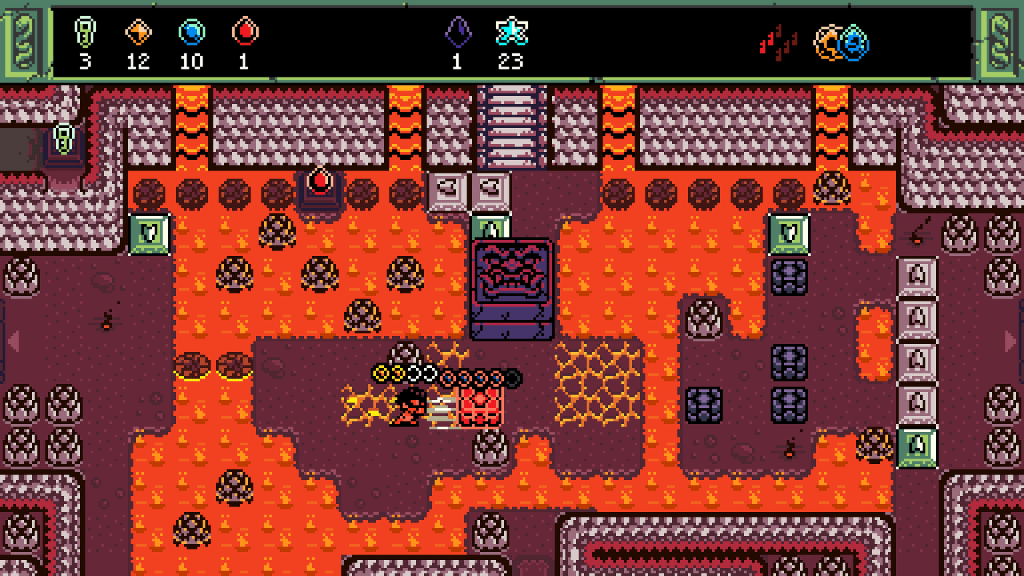

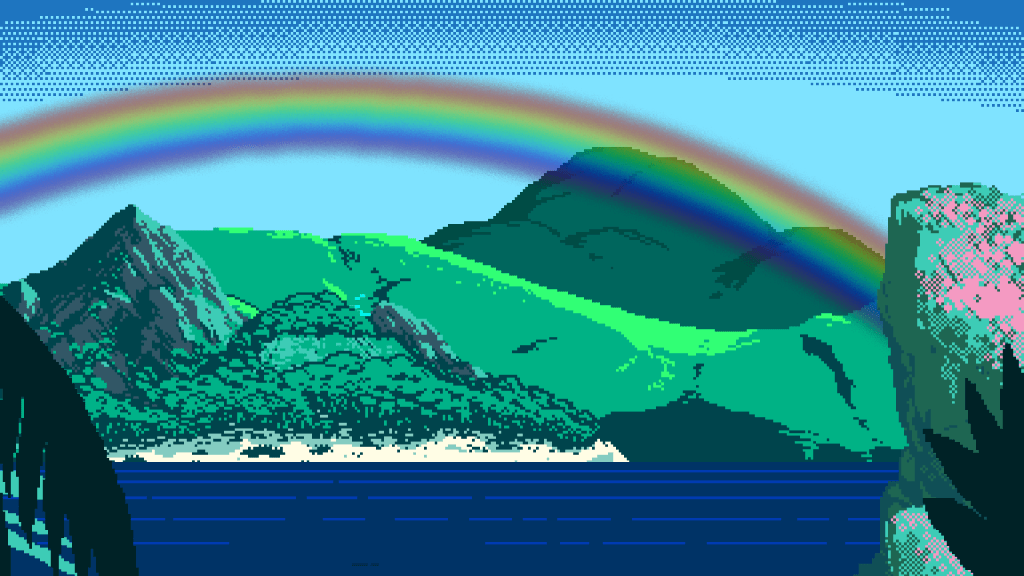

But you won’t mind, because from the highest peak of the Frozen Spire to the shoreline of the Tidal Reef, the titular isles make a glamorous getaway location for the battle-weary video game-liker. The artful, Game Boy Colour-esque pallette, pleasingly chunky 8-bit-inspired pixel art, and beautiful, airy ambient soundtrack (reminiscent of Donkey Kong Country’s seminal score) make for a happy hang-out place, and the light-touch of the game’s purely visual storytelling adds a lovely little dusting of narrative flavour. There are lots of little optional islands to discover too, linked by a charming world map (all sparkling blue waters and fluffy white pixel clouds) that you can explore, delightfully, on the back of a giant turtle. The cosy, feel-good vibes are strong with this one.

On-land, character movement is restricted to four directions as you take on single-screen challenges (with flick-screen transitions) housing a variety of mandatory and optional puzzles. There are no action buttons, so your only method of interacting with the world is to push things—one tile at a time—to solve puzzles by creating pathways to new exits, or one of the many collectable items, depending on the objective. The game quickly introduces layers of complexity to make things more interesting: locks that require keys, coloured gongs that smash matching coloured blocks, pressure plate switches, and hazardous traps that must be avoided. Each of the main islands also adds a few thematically appropriate wrinkles (that I won’t spoil) to further furrow your brow.

Thankfully, there’s no real sense of peril beyond your own lack of puzzling smarts (a significant danger in my case)—triggering a trap or falling to your doom will see you instantly plopped back to the previous square on the grid. It’s all very relaxed and player-friendly, with an unlimited turn-by-turn rewind function just a button press away, and another to completely reset a puzzle if, like me, you frequently bumble yourself into an idiotic corner.

You’ll quickly learn that some solutions require entering from another (currently unreachable) location, and you’ll find unfamiliar objects that seem impassable and mysterious puzzles that appear unsolvable. This is all by design, and you will often leave a screen with puzzles unresolved and collectables tantalisingly out of reach. Over time, you’ll unlock new abilities and gain knowledge that, in classic Zelda or Metroid-style, allow you to return to old locations to solve previously impossible problems and reach formerly inaccessible areas.

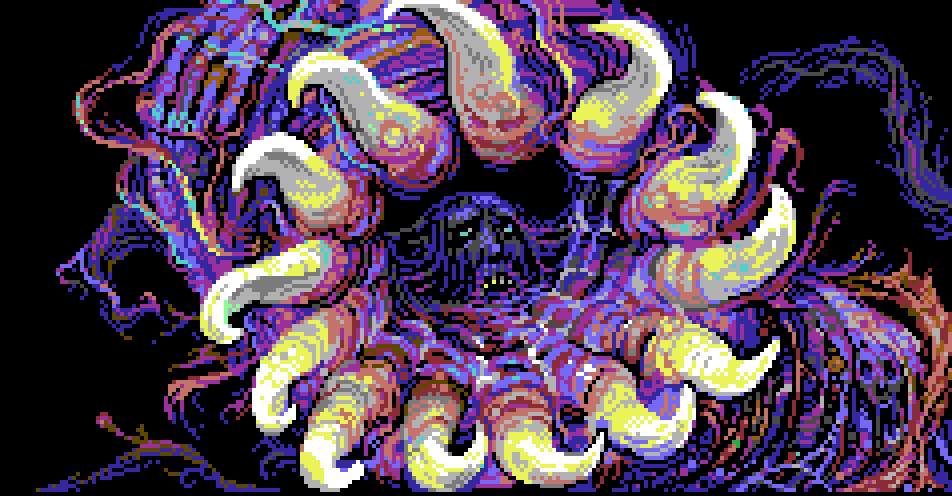

As with all games that play this trick, there is an undeniable pull in the mystery of the unknown (hmm, how do I get over there?) and an almost lizard-brain compulsiveness that comes with the gradual mastery of a space (ah, that’s how you do it!) And you feel it in this world too, as you slowly decipher its mysteries block by block, tile by tile, as if solving one gigantic world-sized puzzle constructed with Lego-like meticulousness. You can almost sense a mathematician’s hand in the needle-like precision of its design, the product of a mind that has, well, spent years designing hundreds of Sokoban-style block-pushing puzzles. It’s also this structure, however, that leads to an issue at the heart of this game that it struggles to overcome.

The secret to good puzzle design is hiding the juicy ‘eureka’ moments beneath enough layers of obscurity that finding the solution feels like a genuine intellectual victory. In my mind, I’m in a fictional battle of wits with the designer—a maniacal, Riddler-esque villain—and it’s this imaginary conflict that keeps me going. Difficulty is all part of the fun, and I will repeatedly bang my head against a challenge out of sheer stubbornness—no matter how thick the brick wall, my head must be thicker! Wait…oh, never mind. Anyway, I will happily endure the pain, safe in the knowledge that the solution is right in front of me, and that the game has given me everything I need to find it. Unless, of course, it hasn’t.

Due to its metroidvania elements, when you’re really struggling with something, it can be difficult to shake the nagging sensation; what if I don’t have what I need?And for these puzzles that require an almost scientific, trial-and-error approach, it’s a very unwelcome dose of ambiguity. It also means lots of wandering about, figuring out what you can solve, rather than doing the solving. And the cerebral, almost mathematical approach needed to overcome its considerable challenges is a very different headspace than the curiousity-driven, exploratory mindset encouraged by an open-world Zelda-like adventure. There’s a tension between these two modes of play rather than a synergy, and it can often fail to fully satisfy in either. You’ll frequently find the reward for your exploration is yet another dead end, for example, rather than an exciting new discovery, and you’ll become more accustomed to tolerating slaps on the wrist than enjoying moments of triumph.

Thankfully, the puzzles themselves are generally very good, but the nature of its Sokoban-style gameplay means that you don’t often get those big, dopamine punch ‘aha!’ moments that that make some puzzle games so rewarding—it’s not one or two clever moves that provide the solution, but thirty or fifty, and you’ll sometimes have to work a little too hard for the pay off. There are smaller, bitesize challenges (which were often my favourites), but many puzzles are sprawling, complex things that fill the full 16:9 spread of your display. I spent over an hour on one particularly tough screen, and after finally putting it to bed, the only thing I felt was tired. When my reward was yet another puzzle with added complexity, I had to step away.

There is undeniable pleasure in the slow untangling of a full screen of blocks, switches, locks, and keys, but this is not a game for the impatient. It’s a slow burn and doesn’t yield its rewards easily, but the satisfaction of taking apart this impressively designed puzzle-box world does grow over time. And you will eventually learn to speak its language too—to determine at a glance what you can and cannot do yet, removing the pang of uncertainty—and in its back half, the game really comes together once most of the roadblocks have been removed. It’s also a remarkably generous package jam-packed with optional puzzles and collectables (and even entire islands), so there’s plenty to do past this point, and a built-in narrative incentive to go for 100% completion. It never becomes a cosy, relaxing experience due to the intense focus it demands, but I did find a nice, methodical rhythm in its end-game.

It’s a tricky time to be releasing a puzzle game with Lorelei and the Laser Eyes dazzling critics with all its Professor Layton by way of Suda51 chic, and the rapturously received side-scrolling puzzler Animal Well having something of a moment. Over the last few years, the micro-genre of Sokoban-inspired block pushers has also been elevated to new heights with the whip-smart Baba is You making the building blocks of the game itself part of its gameplay, and 2023’s Void Stranger inspiring genuine awe with its unfathomable depths lurking beyond the fourth wall. Isles of Sea and Sky is a work of impressive scope and complexity, and a remarkable effort from a very small team that also deserves recognition. But the bar is just impossibly high. It is a good puzzle game, but it’s about to set sail in an ocean of great ones.

If you’re a hardcore Sokoban-head, or if you still go to bed dreaming of Chip’s Challenge thirty years on (first, seek help), then dive into its waters headfirst and without hesitation—you’ll find plumbing its considerable depths a joy. For everyone else, it’s a game best enjoyed slowly, to be nibbled at over small sessions, rather than devoured intensely. Appropriately, given its Game Boy aesthetic, it’s a game that belongs in your hands where you can more easily parse the full scope of its screen-filling puzzles, rather than blown up on a big TV. A game to be played for an hour or two at a time on a Steam Deck then, perhaps on a lazy Sunday morning, or with a warm drink before bed. To dig myself out of the ridiculous biscuit analogy hole I’ve written myself into, think of Isles of Sea and Sky as a Malted Milk. Easy to like, but difficult to truly love. You’ll be glad to have it in your selection, but sometimes, you just won’t be in the mood.

7/10

(A copy of Isles of Sea and Sky was provided for review by Cicada Games)

Isles of Sea and Sky is available now on Steam

Leave a comment