Licensed games got a bad rap in the PS2 era. When gaming hit mainstream critical mass in the West with the original PlayStation, the floodgates opened for a deluge of cynical and cheaply made licenced cash grabs, as publishers took advantage of the PlayStation’s ubiquity in family living rooms to sell to a new casual gaming market which had more disposable income and was less consumer-savvy than the average enthusiast nerd. Every entertainment property that had flirted with the mainstream was represented in some half-baked form, as companies realised you didn’t have to spend time and money developing quality games to sell copies; just slap a popular brand on the cover and away you go. For a while, you couldn’t move for these games, which filled the shelves of any shop with an entertainment section. Going into a store in 2000 and finding a copy of Vagrant Story or Suikoden II was pure potluck, but you can bet they had a hundred copies of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

It created a cloud that hung over the heads of licensed games which took years to dissipate. As a result, a lot of good games didn’t receive the attention they deserved, were seen as somehow lesser, and were simply overlooked. Licensed anime tie-ins were plentiful in this era and were often tarred with the same brush. Samurai Champloo: Sidetracked was never released in Europe, but its relative obscurity in the States suggests it met the same fate, and one it didn’t deserve.

The game is based on the anime by Shinichirō Watanabe, the creative director of Cowboy Bebop. I did my due diligence and watched five episodes of Samurai Champloo to get a feel for it. It’s your typical early 2000s blend of hyperviolence, philosophical sermonising, and casual misogyny, but propped up and carried by the same breezy cool that characterised Cowboy Bebop. It’s a story about youthful rebellion in defiance of authority, following a trio of protagonists in an uneasy alliance, equally happy to fight each other as they are to fight the power. The standout element is its unique blend of styles—a fusion of Edo period samurai drama and contemporary hip-hop culture with a wilful disregard for genre tropes, Japanese history, and its own sense of tonal consistency. It is a show explicitly about mixing up dissonant elements to complement its irreverent vibe; the word ‘champloo’ literally means ‘something mixed’. A post-opening credits disclaimer reads, in a graffiti scrawl, “This work of fiction Is not an accurate Historical portrayal. Like we care. Now shut up and enjoy the show.”

It’s an unusual property to receive a video game adaptation, even if its focus on violent combat seems well-suited. Stranger still is the team chosen to make it. I can’t imagine that ‘punk’ designer Suda51’s Grasshopper Manufacture—straight off the back of avant-garde fever dream fuck ’em up Killer 7—would have been the first name that came to mind for a project like this. There were any number of studios with a track record of faithful and competent adaptations of manga and anime properties, but I suppose if you want someone who typifies the show’s themes and rebellious creativity, then really, who else could it be? With Suda’s trademark style of artfully blending the mundane with the surreal, breaking the mould of accepted conventions, and deliberately making games with a willful rejection of current design trends, the pairing begins to make sense. Suda has been quoted as saying he dislikes working on other people’s properties, and while it’s possible that Sidetracked was a necessary move to boost the coffers after Japanese audiences rejected Killer 7, I prefer to think that he felt a kinship with Samurai Champloo‘s tonal discordance, and from the moment you boot the game, it certainly feels like his heart was in it. This is every inch a Grasshopper jam.

The game is a side story to the show’s main plot, with a separate but overlapping campaign for each of its two titular samurai, Mugen and Jin, with a third campaign unlocked on completion. Structurally, it is standard action-adventure stuff—fight through linear combat stages, defeat end boss, watch cutscene, repeat—but that’s not what makes it unique. Grasshopper has taken the show’s distinctive style and run with it, pushing its more imaginative elements to the fore while injecting plenty of their trademark flair for the absurd. The tone is more irreverent, the visuals more abstract, and the stylistic hip-hop jacket worn by the show is made a more critical component of the overall design, infused into the game’s mechanics and ever-present UI.

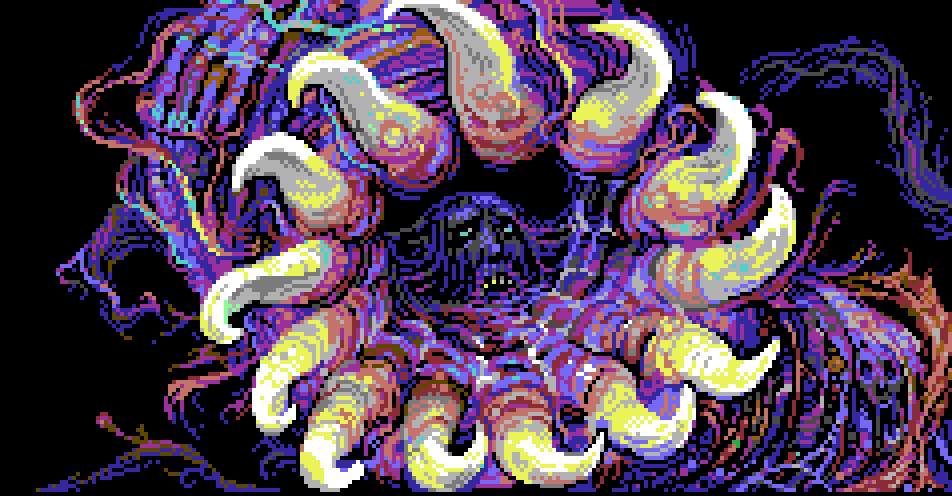

Whereas the show is content to play its plot fairly straight (and keeps its weirder parts mostly on the aesthetic fringe), there is no such restraint shown here. The world of Samurai Champloo (the anime) is a playful depiction of reality, but it never strays into the supernatural. Sidetracked goes fully off the rails almost immediately. In this world, a dream-dwelling witch force feeds a magical snake down a man’s throat, a talking ninja monkey monologues on his deathbed, angry men lose their hearts and turn into demons, and rain is red simply because it looks cool. If you’ve played a Grasshopper game before, you likely already know if you’ll be into it.

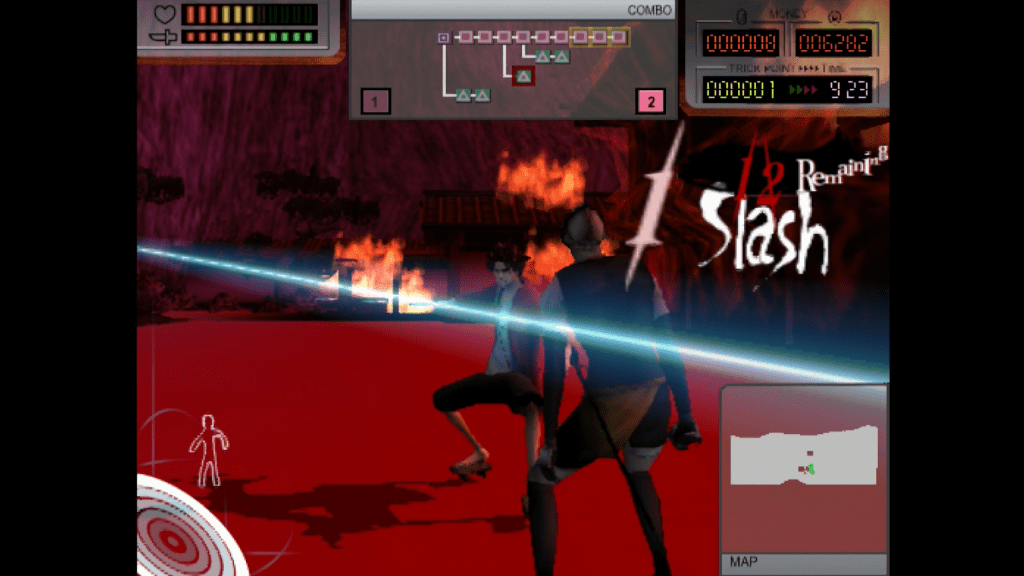

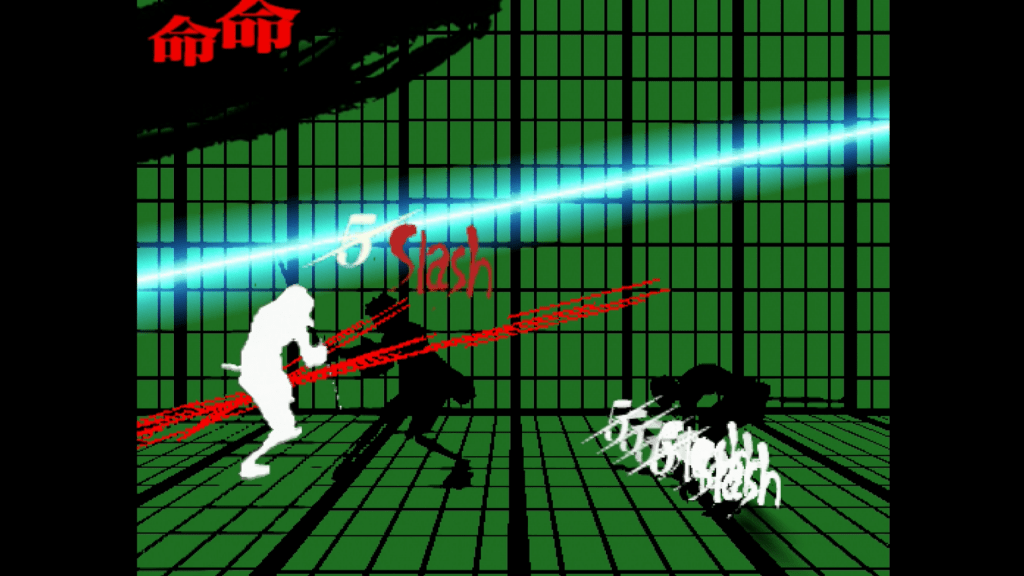

During play, it’s an explosion of creative audiovisual energy. Camera shots cut to the sound of a record scratch as the screen transitions in a glitchy analogue wipe. Combo trees dictated by the beats of collectable vinyl records scroll over a UI built from DJ decks, accompanied by a manic dancing sprite bouncing along to the music in the corner of the screen. In combat, defeated enemies become red, untextured 2D sprites at the moment of impact; the sky turns black as they split apart with a wretched screech before erupting in a shower of shiny collectable coins as your ‘tension’ meter fills.

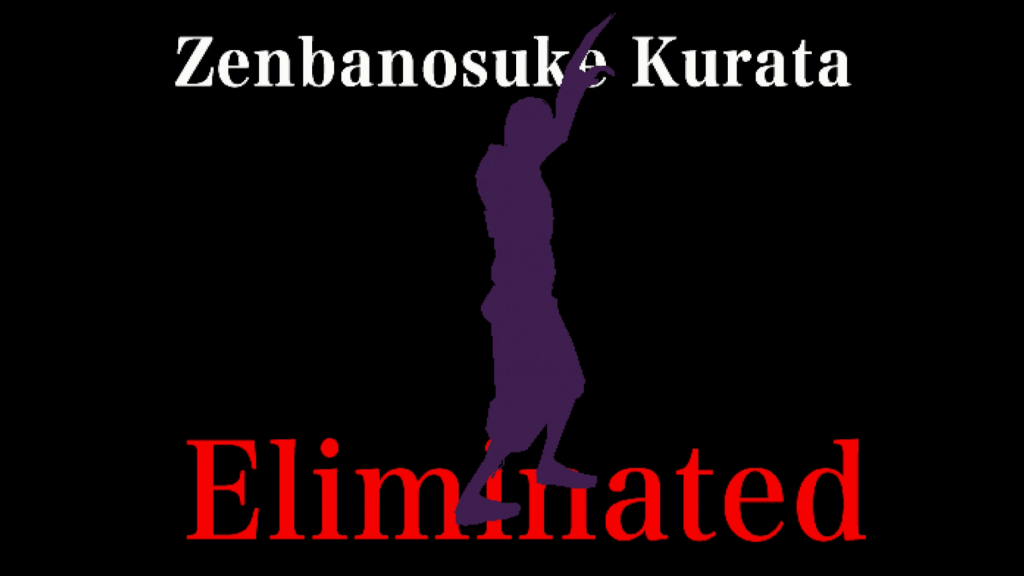

Building the meter unlocks Fury mode, where the screen turns blood red as you dance between defenceless enemies in a screen-clearing flurry of strikes. Max out your tension, and you activate Tate mode. The background fades, replaced by sliding shoji doors adorned with traditional artwork, as you begin a frenzied assault on a single hapless enemy. There’s no finesse here; just mash the buttons to hit as many strikes as possible within a time limit. It’s pure “Track & Field” button-bashing energy with no intent beyond getting your blood pumping. Hit 100 strikes, and it escalates even further as you enter Trance mode. Backlit by coloured light, your character becomes a black silhouette, and full control returns as your blade dances around one hundred enemies in a frenetic samurai disco to a high-tempo eurobeat soundtrack.

Clear the stage and a treasure chest pops, awarding you a new sword or piece of collectable artwork. The record scratches, the screen wipes, and you’re back in the level wondering what the hell just happened. Then you do it all again. The combat is a ludicrous procession of ever-escalating violence and an explosive sensory overload that never stops being fun. It’s not particularly deep, a little mechanically loose, and certainly lacking in polish, but the focus is squarely on the experience of playing rather than the playing itself.

The game is not entirely devoid of nuance, however. Some (mostly) well-designed boss fights require more finesse, and a viciously snaking difficulty curve makes getting to grips with the more technical elements of the combat system essential for some encounters. It rarely puts as much strain on your fingers as it does on your eyeballs, but there is some scope for skilful play. If you’re looking for mechanical sophistication though, you’re better off elsewhere. That’s not why you come to Grasshopper.

Many action games sacrifice mechanical depth or responsive controls at the altar of visual fidelity, immersion, or narrative. It’s a pursuit that often sits poorly with me—if you’re going to compromise gameplay, you’d better make damn sure it’s worth it. Grasshopper’s approach with this game is similar; everything is secondary to creating a vibe, but with the promise that you’ll have an experience unlike anything you’ve played before. When frustrations over spotty hit detection or wonky level design threaten to spoil the fun, they suddenly fade away when, out of nowhere, you’re smashing skeletons in a 2D side-scrolling Mario parody through a bootleg, melting Mushroom Kingdom. Complaints of style over substance may well be apt, but they would be missing the point entirely—when it comes to Goichi Suda, the style is the substance.

Leave a comment