Sometimes you play something new and it feels like a moment. Like you’ve discovered something special before the internet has discussed and dissected it, and before the weight of any cultural impact can be measured. Where there are whispers, perhaps, but it feels like you are part of a conversation that hasn’t happened yet, and one that you know is coming. I felt like this the first time I played Larian’s Divinity II in 2007, The Witcher in 2008, Demon’s Souls in 2009, and Nier in 2010. Not all of those games were great, but you could feel the raw potential, and a buzz of building momentum, signalling a budding talent and an exciting new beginning. 1000xRESIST from first-time indie studio sunset visitor 斜陽過客 is a stunning debut and a far more accomplished work than Larian or CD-Project Red’s fledgling titles—it’s a narrative masterpiece in its own right—but it also feels like one of those moments.

1000xRESIST is a singular work that bears comparison to Disco Elysium in how its creators have leveraged a grab bag of non-video game-related influences to create something that’s just… different from most other games. sunset visitor 斜陽過客 is a small studio comprised of a majority of Asian-Canadian diaspora creators with experience in dance, theatre, music, film, visual, and new media arts. Their game is the result of a collective looking outside the medium to find their inspiration, and you feel the richness of this team’s palette, swirling with the colours of lives devoted to the many forms of artistic expression, creating a work that captures a wide range of human experience. The result is exceptional; a staggeringly ambitious narrative-driven sci-fi epic with a gripping story, striking cinematic visual design (that belies its meagre budget), beautifully written dialogue, and outstanding performances from a very talented voice cast. 1000xRESIST is a brilliant video game. But it’s also a powerful piece of interactive speculative fiction that transcends its medium to stand simply as a great work of art.

The Nier games are possibly the closest mainstream comparison, and an easy cultural touchstone to point to. There are similarities, after all, in the broad strokes of its high-concept sci-fi setting, the frequent perspective shifts, and willingness to play with structure in interesting ways. There are parallels too in its themes. The Nier games luxuriate in big questions about the nature of humanity, philosophy, our past and possible futures, and crucially, have something to say about them. 1000xRESIST has enough similarly big ideas to satisfy on the macro level, but also zooms in, sometimes uncomfortably close, to explore much smaller, more personal questions. It reckons with issues that feel viciously contemporary—real concerns of real people that are knotty and nuanced, and it explores the depths of human pain and trauma with a scalpel rather than a sledgehammer. It cuts deeper than Yoko Taro’s works and is more meaningful as a result.

It uses well-established sci-fi tropes but deploys them with uncommon creativity to tell a story that exists simultaneously as an allegory of Chinese and Hong Kong diaspora politics, an exploration of the loss of home, history, and culture, the cost of resistance and the fight for basic freedoms, and a deeply personal study of the effects of intergenerational trauma in diasporic families. That the game manages to have these conversations with the player in a way that feels rich and deeply human, while telling an original fifteen-hour sci-fi narrative with all the twists, turns, and galaxy-brain mind-fuckery you could possibly want from his genre, is astonishing.

The setting for 1000xRESIST is the stuff of classic sci-fi. The planet’s surface is a glowing red wasteland, decimated by a centuries-long war with an alien species known as the Occupants. Humanity, as we know it, is dead—wiped out by a deadly disease spread by the invaders. We enter the story one thousand years later in a subterranean city known as the Orchard. The city is populated exclusively by clones of a woman called Iris, known as the ALLMOTHER, who is not only immune to the virus but also an immortal, god-like figure to the clones. The ALLMOTHER is far away from the Orchard on ‘The Other Side’, fighting a never-ending war against the Occupants on the surface. Despite her absence, the clones serve her unquestionably, hoping they might one day be chosen to join her side.

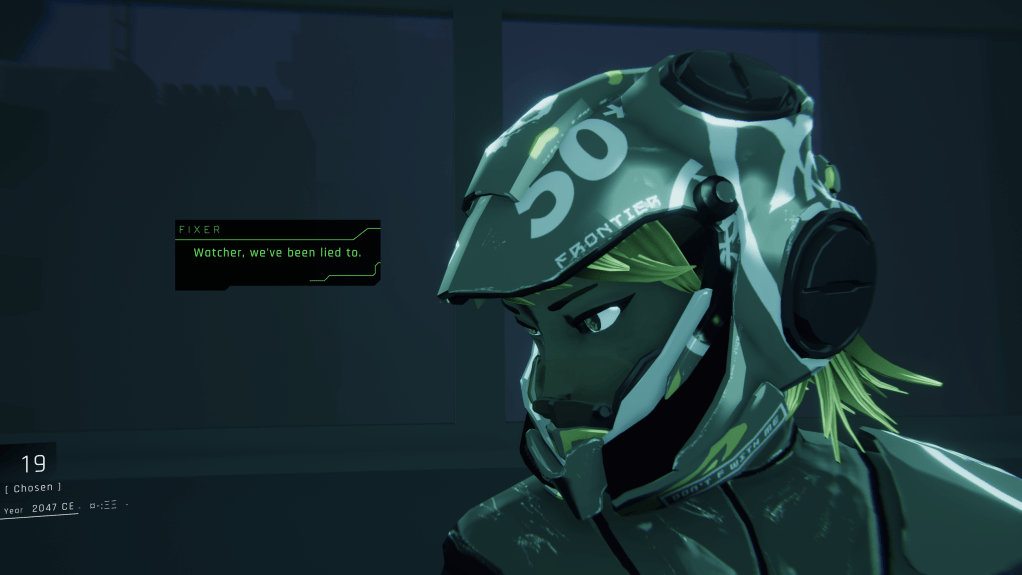

The Orchard is governed by six sisters who provide the essential functions necessary for its continuation: Bang Bang Fire, head of defence. Knower, keeper of knowledge and history. Fixer, charged with keeping the Orchard’s complex machinery running. Healer, the city’s doctor, surgeon, and cloning supervisor; and Principal, who has oversight of all other functions. Our protagonist is Watcher, whose role is to enter into scenes recreated from the ALLMOTHER’s memories (by a mysterious AI companion known as Secretary) and to interpret them for the other sisters through a process known as Communion. But there’s also a more sinister side to Watcher’s role: to commune with her sisters and watch for signs of dissent or disloyalty to the ALLMOTHER. If a sister is found to be wavering in her devotion, she is labelled as treasonous and swiftly executed.

In a striking pre-title card sequence, we see Watcher brutally murder the ALLMOTHER, and what follows is an exploration of the one thousand-year history that led to this moment—from first contact with the Occupants and the slow death of humanity, through the creation of the Orchard and the clone sisters, and the events that caused Watcher to turn on her maker. Running alongside this is the game’s most potent narrative thread and the real beating heart of the story—an intense character study of Iris, the ALLMOTHER, by excavating her past through Communion sequences, exploring the pivotal moments in her life and that of her friends and family.

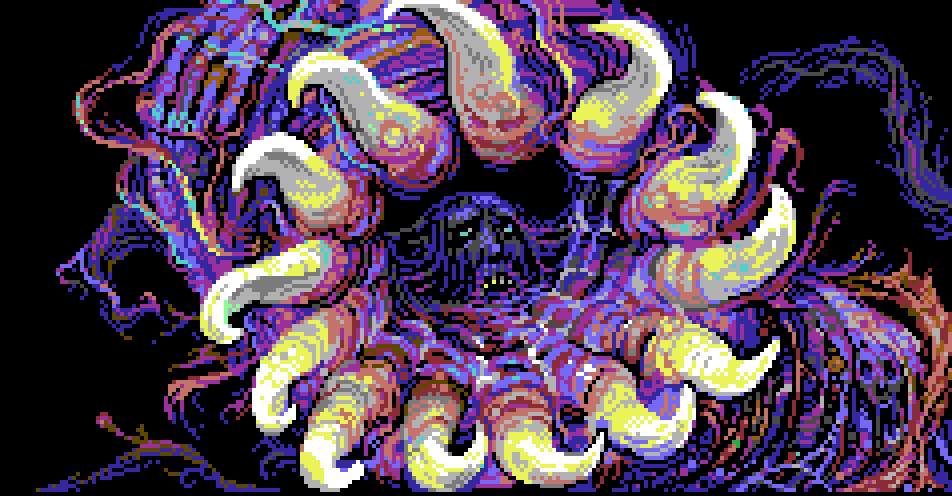

The Communions play out like interactive dream sequences—hazy, fractured memories of real events, sometimes hundreds of years past, shotgun blasted back into reality from an unreliable source. It’s where the game offers its most creative visuals, storytelling, and gameplay, utilising frequent perspective shifts—from third-person over-the-shoulder exploration and first-person walking-sim style sections, to top-down, side-scrolling sections, and even some recurring Gravity Rush-esque flying sequences—as you explore a series of mostly static three-dimensional vignettes. Interactivity is light, rarely requiring more than exploring the environment and interacting with a certain character or object to trigger the next link in its narrative chain. There is some occasional (very light) puzzling—teleporting back and forth through scenes along a timeline to find the way forward—but it’s otherwise an entirely visuals and dialogue-driven experience.

It’s through these sequences that we are introduced to the people in Iris’ life, their experiences living as Asian immigrants in North America, the impact this has on them, and on shaping the woman Iris will become. We are walked through an exhaustive account of the immense pressures of living abroad in a society that is actively hostile to you, and the toll it takes on a person’s physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing to conform. It surfaces the loss, pain, and grief that a person takes with them (and that they leave behind for others) when they move away. It also explores the circumstances that often mean people don’t have a choice (Iris’ parents leave Hong Kong as a result of political violence). It then goes to painstaking lengths to explore the trauma that Iris inherits and then perpetuates, with tragic consequences.

Despite its enormous scope and the heaviness of its themes, 1000xRESIST paints its big sci-fi canvas with delicate brush strokes, depicting intimate, often mundane moments that are charged with meaning and grounded in a reality that we recognise. It makes for very effective (and affecting) sequences that are still bouncing around in my head days later. These scenes also reward in surprising ways, and the writers are just as interested in presenting you with twists on classic sci-fi concepts to chew on as they are in exploring real-world issues, and you’ll frequently find memorable moments tucked away at its edges. In an early scene set in a school, a busy student (and one of many NPC characters filling its halls and classrooms) wishes out loud that she could make copies of herself to get more done. Watcher casually asks, “Would you be kind to your copies?” This throwaway line caught me completely off guard, and I sat for a few minutes just thinking about it. In moments like this, when small discoveries impact you in surprising ways, you realise you’re playing something special.

Between Communion scenes, you’ll spend time in the Orchard exploring its (slightly bewildering) architecture, speaking with its inhabitants, and getting to know the other sisters. It’s here you’ll learn more about the ‘now’ of its fiction and drive the present timeline ever closer to the climactic killing in its opening cutscene. It’s a clever narrative conceit that has you playing armchair detective ‘outside’ of the game, analysing the present for the reverberations of the past you have just witnessed during Communion. (And the rivers run deep, for those of you who enjoy this kind of narrative archaeology.) The gameplay in these sections is simplistic—like exploring an old-school JRPG town—with NPCs standing around waiting for your arrival to deliver a few lines of dialogue. It can occasionally be dull and repetitive, but is elevated by the consistently excellent writing and the desire to learn more about this society, as you begin to uncover the dysfunction that lurks under the surface of its superficial utopia. You’ll want to seek out every line of dialogue too; after all, you wouldn’t want to miss the NPC whose job is to assign all clones their functions based on their colour in the gestational pod, only for them to discover, possibly after centuries of work, that they’re colour-blind.

It’s here in the present day where we return to the themes of culture, history, art, censorship, and control. With the ALLMOTHER away, the Orchard’s clone population seeks to make sense of their lives by obsessing over what Iris left behind. Primarily, a single poem constructed from cryptic language and peculiar phrases. The clones obsessively analyse the poem, extracting meaning that couldn’t possibly have been intended, and use it as the basis of their society, governing their belief systems and behaviours. The clones repeat a handful of nonsense phrases from the poem over and over in different contexts, imbuing them with meaning that we eventually come to understand:

Six to one. Red to blue. Sphere to square. Hair to hair. Hekki Almo.

It’s a fascinating detail in a future where life has been stripped back to its essentials—people no longer have names; just functions, they no longer eat for pleasure, all faces look the same, and burying the dead is seen as an inefficiency—that the clones still seek to understand their world and their place within it through art, as if this pursuit is as essential to human preservation and survival as breathing. And it’s another key theme that the story explores in detail: that it’s through art, culture, and media that we write our history and understand our present, and that those in control of it hold incredible power. Throughout the game, we see theatre productions depicting pivotal events in Watchers’ life that we have witnessed first-hand. The actors sensationalise, stretch, and exaggerate the truth. They lie, and we see the fiction later become truth. It asks what happens when art or culture is lost, destroyed, misappropriated, controlled, or remade by people who are not its owners and have only self-interest at heart.

As you approach the game’s conclusion, it does not shy away from showing you the devastating consequences of the issues it raises, both for its cast of characters and the society it depicts. It takes some big narrative swings in its back half that really pay off, and for a story with such mind-boggling complexity, the conclusion manages to successfully provide satisfying answers to its labyrinthine fiction, and a searing clarity of message and real world commentary through its imagined future.

In the final scene of the game (which I won’t spoil here), after a series of revelations about the world are imparted to its characters, the game asks you to make a choice: after everything that you’ve seen, what comes next? What will you take, and what are you willing to lose to build the future you want? I made the only choice I could for these characters: that they continue on together. Live together, love together, fight together, resist together, die together. That they might bury the old world, and find a new home in its wreckage.

9/10

1000xRESIST is out now on Steam and Nintendo Switch

Leave a comment